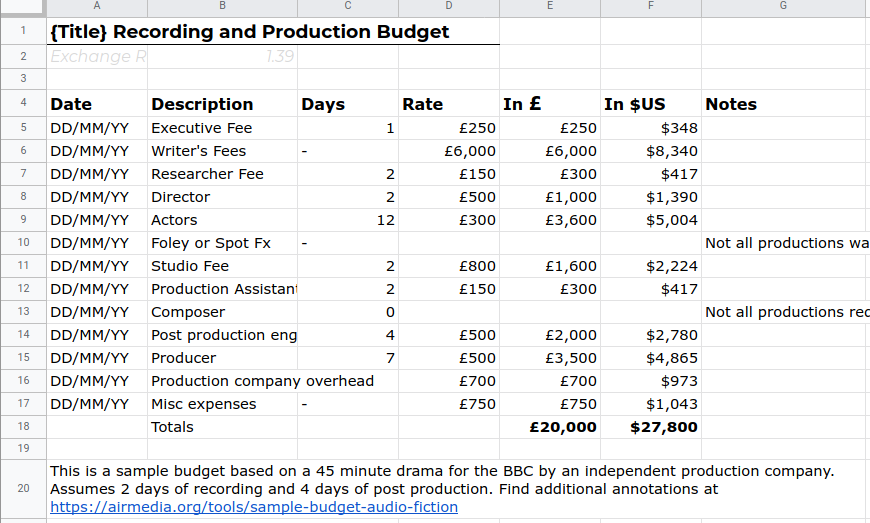

Sample Budget: Audio Fiction

AIR worked with long-time member Jude Kampfner to develop and annotate this sample Audio Fiction budget, based on her experience producing original audio fiction for the BBC. This sample budget is based on a recent project, a 45 minute audio drama recorded in a studio over two days.

Jude led a 90 minute webinar on developing audio fiction budgets on May 18, 2021 Crafting a Budget for Audio Drama. The recorded webinar is available for AIR members to watch on-demand.

Two days is a tight studio turnaround so it requires some planning and efficiency: the notes below detail some of Jude's strategies for making the timing work. £20,000 is a typical budget for a BBC fiction production, so it helps to approach a project with a lens of "What can I do with £20K?" rather than "What will it cost to produce this story perfectly?"

View (and copy) the budget template.

Annotations

We worked together to annotate each line item and add a bit of context. Because all of her figures are in pound sterling, we've added a conversion into dollars for reference. This is a great template for a basic budget, though you’ll probably want to pick one currency.

Executive: Any independent production company registered to supply material to the BBC is required to hire an executive from their approved list to review your project. Their name has to be on the top of your pitch. The executive will assess potential compliance issues in the piece. Their job is to let you know whether or not you need to confer with legal. If you're recording a memoir and the narrator talks about their drug addled ex, the executive will make sure that you know you need to actually track them down and confirm that you're not defaming them. The executive won't defend a production if there's a problem after the piece airs but they're supposed to prevent problems. BBC Domestic often won't even listen to a commission before it airs. They assume it's been vetted by the executive.

Writer: Rates will vary, but often 1/3 of the overall budget will go to the writer. That might seem like a lot, but the writer is crucial and the production will stand or fall on their work. Tip: don't start production until you are happy with the script. The producer and writer work very closely together. It isn't unusual for an engaged producer to have three 3-hour sessions with a writer, even on 45 min play. If you're producing an adaptation, budget for a script writer for the adaptation as well as for the underlying rights. Both have to be negotiated. And expectations about adaptations will vary:some writers will be delighted about the adaptation and excited to read the final script. Others will want to be much more involved. Typically the contract will explicitly state that the writer does not get to sign off on the final recording. In the UK productions are required to pay the writer £150 a day to come to the recording sessions - that is included in the fee.

In the UK, the Writers Guild has established rates for writers working on BBC productions. In the US, agents often have less of a foundation to work from. WGA-East is organizing in this space, but they don't have established agreements in place. US agents often expect a lot of wrangling, especially if they're used to film work.

Researcher: Research needs might include background on an historical period, so that actors have context for their characters, or to add interesting details like "What would traffic and church bells have sounded like in Prague in the 70s". Always plan to have more detail available than is actually written into the story.

Director: Sometimes the producer also directs, some producers strongly prefer to direct. Even if you'd rather direct, collaborating with a director and watching them work can be a real professional development opportunity. A local director will know the local acting community well and might have an idea for an ensemble cast. Casting can be collaborative, but usually the director will be responsible for casting. This sample budget assumes the director is casting the production.

Actors: This budget assumes six actors for two days. Expect to pay more for the first day, to cover reading the script and getting to know the character(s). Although most director/producers dispense with a read through however exciting that may be. Actors with smaller roles often read multiple characters and join in crowd scenes. Expect to pay more for lead roles, less for smaller roles. Typically an actor needs at least $200 to make the trip to the recording studio. BBC productions require you to use equity actors, but in other cases you can sometimes work with student actors or community theater groups to keep costs down.

The union expects actors to have a full hour for lunch. Often engineers think an hour is too much and they would rather be working, so sometimes while the actors are out eating, we'll record footsteps and doors.

Expect to provide lunch. Some indie companies have begun to cut costs by making it clear that actors will be responsible for their own lunches, but you’ll lose a lot of conviviality that can help a production gel. Audio drama is intense and long days in the studio are draining. Breaking bread together makes for a more energetic afternoon.

Spot Fx or Foley: A really good foley artist will energize the cast and save a lot of time in post production, but they aren't all great. Budget for foley in a piece that has a lot of realism and action. Expect to pay £750 – £1000 for a good foley artist.

Studio Fee: If you bring your own engineer and just use the studio (this is known as a "dry hire") that can be cheaper than hiring the studio's engineer, but that isn't always true. A less transit accessible studio is sometimes cheaper but you'll end up paying for taxis to get folks there. Some studios will let productions use corridors, stairs, roof deck, or the street outside to record, using portable equipment. Studios in a busy commercial building may balk at the disruption to other tenants during business hours. Consider working at weekends - most actors are open to this.

Plan your timing to make the most of your studio time. Group actors in scenes rather than recording in sequence to get the most out of everyone’s time and as well as the studio rental.

If a piece has lots of narration, consider booking a smaller studio for that and bringing the actor in separately. Audio book studios often have small booths that are perfect for recording a narrator.

Production Assistant: In the studio, an assistant is indispensable. There will always be a few actors who didn’t bring their script or tablet. The production assistant can let folks in, make sure everyone has scripts, and order lunch. Having a PA can feel like a luxury, but without one the whole production has to stop to answer the door or get lunch set up.

The PA can also be tasked with formatting the script for the actors, ensuring that lines are numbered (So it is easy to “pick up at line 8 on page 4”) and there aren't orphaned lines, and then making sure that scripts are delivered to agents and actors.

A PA is also vital for scheduling. Recording the lead characters first and grouping actors by scenes is a much more efficient use of time than recording chronologically, but it can definitely create headaches if you’re not impeccably organized. A PA can help you make sure that actors are scheduled to be in the studio when you are ready to record their scenes.

Composer: Not all pieces will warrant a composer. AIR’s rate guide includes some suggestions about what to expect to pay to license music or commission a custom track. The best way to get original music is to ask a composer you know well for permission to use music from their backlist for musical phrases, bumps and bridges between scenes.

Post Production Engineer: An experienced mix engineer will often also handle sound design--this budget assumes one engineer doing both. Many engineers specialize so if they record the drama they won’t always want to mix and vice versa. It’s handy to have one engineer record and mix, but it’s not crucial. Some post production engineers are more inventive and collaborative than others, so it helps to know what you need. A good sound designer will have subscriptions to sound libraries as well as a unique library they've recorded themselves.

The producer and post-production engineer usually work closely together. Typically the Producer will sit in the studio for an initial rough mix and then make comments on mix drafts remotely. The producer needs to know which takes to keep or you’ll waste studio time going through the takes together. Expect to let the engineer know which takes you’ll want to use before you sit down together.

Many engineers will have amassed their own sound library of atmospheric noise and other sound they’ve recorded over the years. These personal collections are often very helpful. Sound libraries are often much too prescriptive -- the sound you need is often not described accurately in a library and listening through clips is time consuming. Often sounds are invented in the studio. Some plates jiggling on a table can make a rattling train.

If there are specific sounds you need and your engineer doesn’t have them, you can also pay someone to go out and record. Sometimes you can pay people on the spot to participate by shouting a few words -- an offer of $20 per person is fine if it's really just a few words.

Producer: This is you! Keep in mind that most clients are going to balk if you budget for a rate that is well outside of local norms.

Production Company: Usually the producer owns the production company, so the Production Company fee allows you to put some money into the bank to seed the next production. A new production will begin incurring expenses before any money comes in -- for instance, a writer generally expects 50% up front.

Misc Expenses: Expect to pay for lunch, script printing, insurance among other incidentals. You may find you need to pick up some props.